IMPROVE MY GAME

Articles

How Fast Eddie Generates 150 mph Clubhead Speed over the age of 50

We had the opportunity to evaluate Eddie Fernandes ahead of the Pro Long Drive Association world championships last month. The 2018 Masters division champion still has 220+ mph ball speed potential and is among the most talented long drive competitors the Masters division has ever seen (he’ll turn 52 next month). Not only did Eddie go on to win the PLDA event, he won all five of his sets, scoring 1000 out of a possible 1000 points in the process.

While most golfers aren’t dreaming of 150 mph clubhead speed, we haven’t met a single one who wouldn’t mind a few extra yards off the tee. Studying how the fastest golfers in the world generate speed can be instructive for any golfer looking for more.

We took Eddie through our physical screen, power test and 3D motion capture. Here are three observations from his assessment that stood out:

1) A Powerful Lower Body

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably seen a post from us about the relationship of vertical force and potential clubhead speed. While all golfers push against the ground to generate speed (just watch Justin Thomas, Lexi Thompson, Bubba Watson, etc), maximizing vertical force as a strategy to increase clubhead speed is nowhere more apparent than Long Drive. Look at the footwork of 2017 World Long Drive champ Justin James:

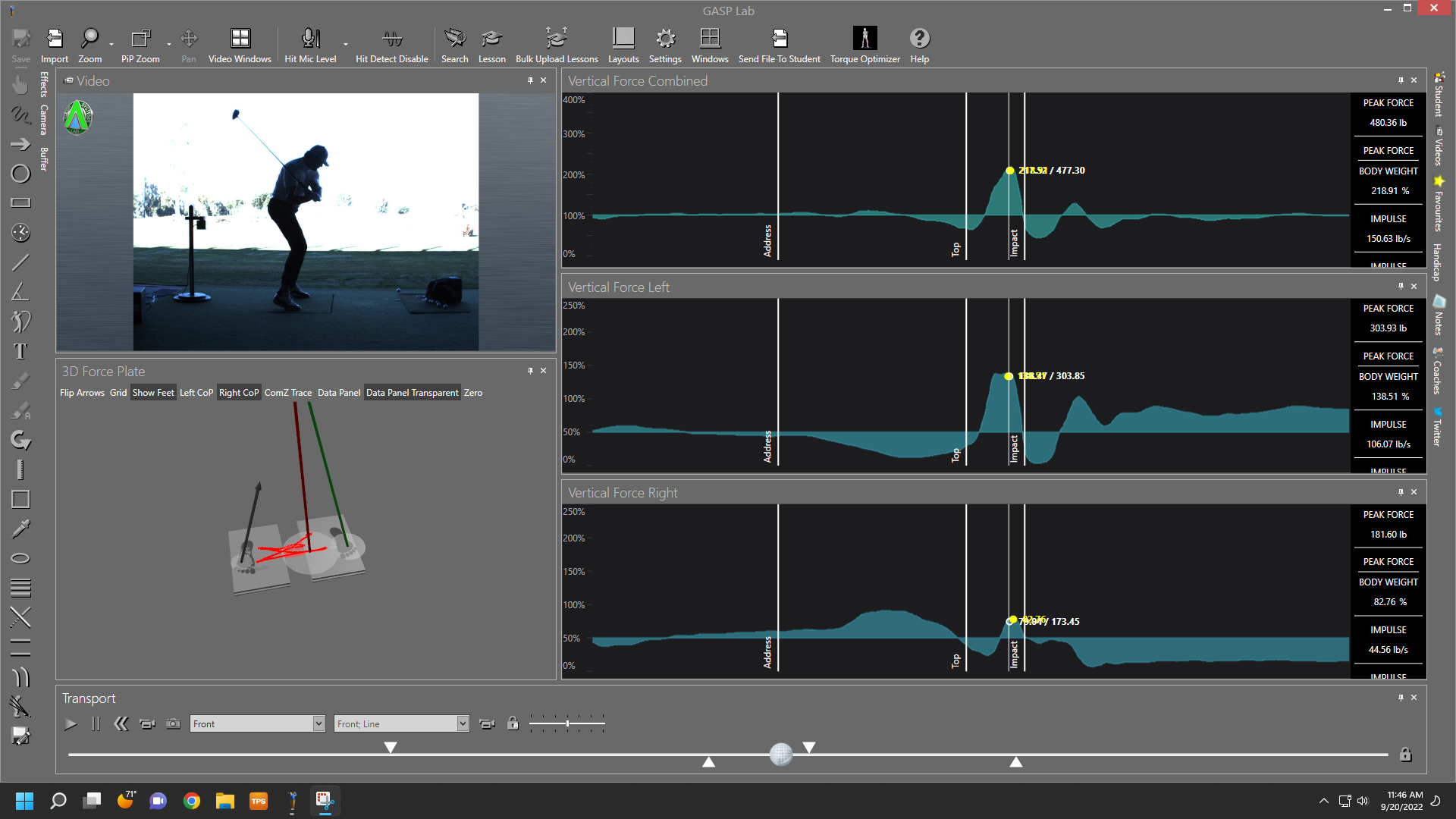

When we evaluate golfers vertical force, we want to know both their potential for generating force (we use a countermovement jump in our power test) and how much vertical force they actually generate in the golf swing (from force plate data).

Despite being taller and heavier (220 lbs) than most professional golfers we’ve evaluated, Eddie’s countermovement jump of 26” exceeds our PGA TOUR average.

Having explosive power in the lower body isn’t very meaningful if a golfer doesn’t use it in their swing. While Eddie doesn't have as pronounced of a squat as long drive competiitors Justin James or Jason Zuback, his force plate data revealed that he generates almost 500 pounds of total vertical force (~220% of bodyweight). Our PGA TOUR average of total vertical force is 198% bodyweight.

When considering the importance of "using the ground" for power, when a golfer generates force is nearly as important as how much they generate. One of the most significant distinctions in comparing data of a high clubhead speed player vs a low clubhead speed player is that we tend to see vertical force spike too late in slow players.

Notice how early Eddie's vertical force peaks in the screen capture above. Most slow (and higher handicap) golfers tend to peak much closer to impact which prevents them from applying that force to the club.

The most powerful, effective ball-strikers in the world tend to apply vertical force earlier in the downswing than most amateurs.

— TPI (@MyTPI) June 21, 2022

If vertical force peaks too late, it's more difficult for the golfer to translate it to the club.

(🎥 via Power Level 3) pic.twitter.com/cZiLDMJ4g7

2) Elite mobility allows him to make large turn with high hands

We often associate declining distance with a loss/lack of strength, but, especially as we get older, a loss of mobility can be just as detrimental.

When we consider how a golfer generates clubhead speed, we can distill it to two primary avenues:

Why is training to improve strength and mobility so beneficial? According to @SashoMacKenzie’s latest research, there are two primary ways a golfer can increase CHS:

— TPI (@MyTPI) July 14, 2020

1) Apply higher force to the club.

2) Apply force over a greater distance.

🎥: via @FunctionalMvmt Podcast pic.twitter.com/CTq40VYykc

If a golfer's ability to rotate is limited, so will be their potential to create a long ramp.

Here’s Eddie performing the Multi-Segmental Extension and Multi-Segmental Rotation from the Top Tier SFMA (a movement assessment we teach in our Medical Level 2 course which helps medical professionals identify painful movement patterns). This is impressive mobility for any rotational athlete, regardless of age.

While this isn't the only reason Eddie can move the club 150+ mph, his elite mobility allows him to make a large turn and get his hands high. By maximizing the distance that his hands travel, Eddie has more time to apply force to the club.

3) An efficient sequence of energy transfer

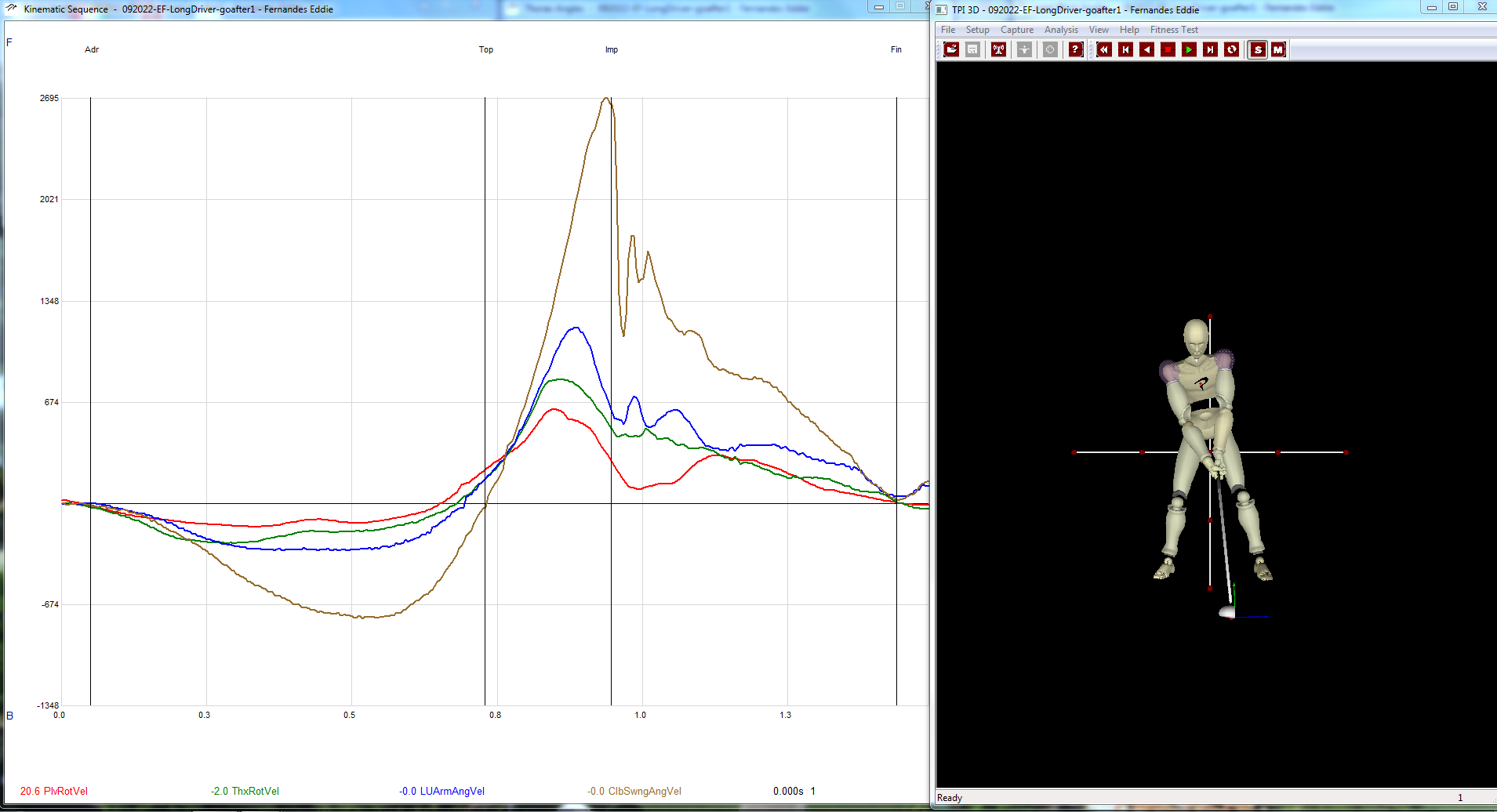

When we want to know how "efficiently" a golfer generates and transfers energy from their body to the club, we look at their kinematic sequence graph. Here's Eddie's:

When evaluating the kinematic sequence of a rotational athlete, we look at three variables:

First of all, we want to know the order that the segments peak in speed. What is the sequence? 1-2-3-4?

Secondly, we want to see how well they transfer energy from one segment to the next. Does it build?

Lastly, we'd like to see how sharply the segments decelerate. We want the deceleration sequence of the graph to create volcanoes, not rolling hills.

Eddie does all three extremely well. Though an efficient sequence is not a prerequisite for a long drive competitor, it does indicate that they are able to maximize power with the least amount of effort, a trait that can be helpful for longevity and durability.

While evaluating Eddie a few weeks before the competition had almost no impact on his success in the event, we think that highlighting his "superpowers" can help coaches and practitioners improve performance in their own athletes. If you'd like to learn more about our evaluation process, check out our Level 1 or Power Level 2/3 Certification courses.